Hollywood fixer Willie Bioff killed in automobile blast 70 years ago

Chicago Outfit associate and union racketeer sang to feds, paid the price

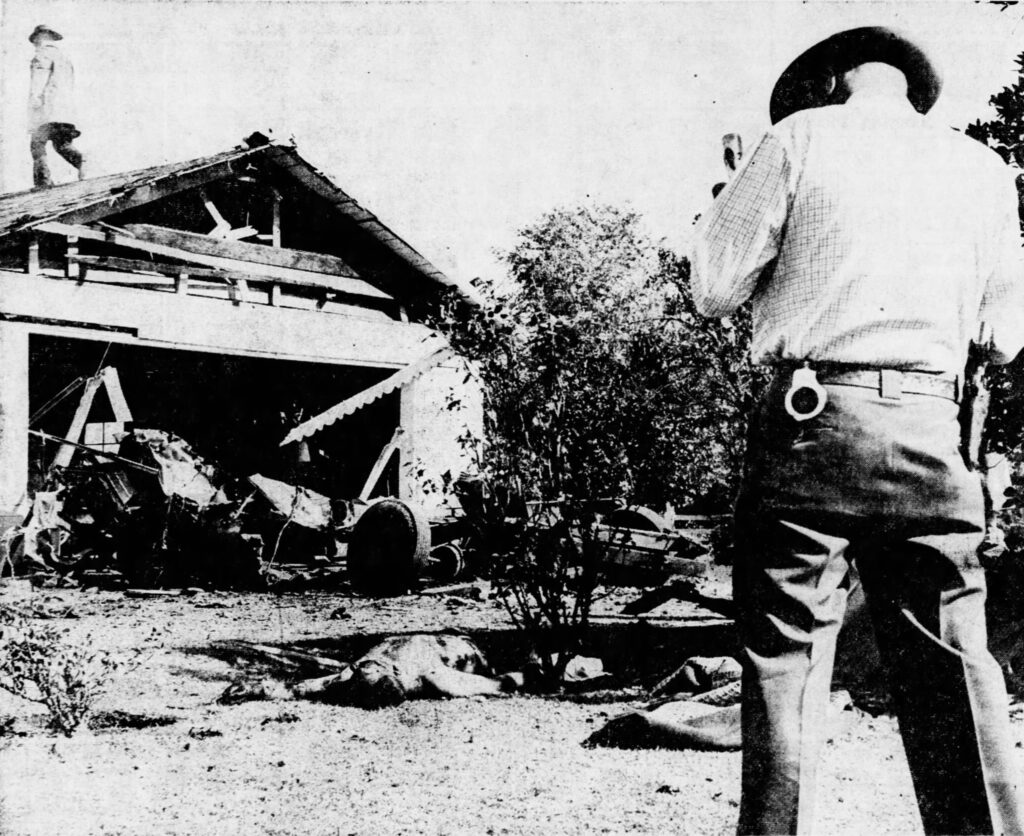

Chicago Outfit associate Willie Bioff rose to power as a corrupt union official, extorting millions from Hollywood studios on behalf of organized crime. In 1955, long after he became a government witness and went into hiding, a car bomb rigged to his truck exploded in the driveway of his Phoenix home, killing him. Although he may have tried, Bioff could not escape from his criminal past.

Born in 1900, Bioff’s family moved from Russia to Chicago when he was a young child. After coming of age, he gravitated toward questionable career paths. He began with pimping and petty hustles in the 1920s but moved into the more profitable labor racketeering by the early 1930s.

Labor racketeer

Bioff teamed up with a pliable union man, George E. Browne, and muscled in on local theater owners using threats of striking projectionists. Their work soon caught the attention of the Chicago Outfit. According to one story, the boss received word about the two when they were celebrating a big score at a club owned by Al Capone’s associate and former bodyguard, Nick Circella, aka Nick Dean. Frank “The Enforcer” Nitti requested a meeting with them, an invitation the pair could not refuse.

In 1997, Vanity Fair writer Nick Tosches offered a different story: Mobster Johnny Rosselli originally schemed to bring in Bioff and Browne.

“At a 1934 Chicago meeting (Browne and Bioff were not invited), Rosselli explained the profit structure of the movie industry, and a plan was laid for a wholesale extortion operation of the major studios” via the International Alliance of Theatrical State Employees (IATSE), Tosches wrote. “Rosselli would operate as the puppet master of Browne and Bioff.”

Backed quietly by the Chicago Outfit, the two discovered a gold mine in Hollywood. Terrified of strikes delaying production, studios would accept any help they could get to keep sets running on time.

As Browne gained influence and power as a recognized figure in the union scene, Bioff, Circella and others took care of the hands-on dirty work of intimidation and extortion. In 1934, Bioff and Browne seized control of IATSE.

Their extortion scheme didn’t always produce the desired effect on the first attempt. Some studio heads held out, although briefly. But the pair honed their tactics so that most studios, big and small, inevitably kicked up the cash.

The fix was simple: Pay up or the cameras stop rolling. The moguls, from MGM to Fox, preferred discreet payoffs to union crises. Bioff, a sharp dresser and smooth talker, played his role well, convincing Hollywood he was not a bagman but a businessman.

In the lucrative racket, Bioff extorted large studios for $50,000 and smaller studios for $25,000.

Extortion scheme revealed

All bad things must come to an end, however, and by 1937 the Bioff-Browne endeavor came under public scrutiny. Then, in 1939, syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler, a vocal opponent of corruption and rackets, revealed Bioff’s old pandering charge and the unusually quick release from jail that followed.

Bioff faced court first in Los Angeles and then was extradited back to Chicago to face charges in early 1940. That, however, was nothing compared with the charges his extortion racket brought.

The federal government handed down indictments on Bioff, Browne and Circella for tax evasion and racketeering. In 1941, the trial began.

“Obedience was never one of Bioff’s strong points,” Alan K. Rode wrote in a piece for Noir City Magazine. “On the stand, he accused studio bosses of bribing him to maintain labor peace — while remaining mute about the Outfit’s orchestration of the scheme.”

The jury didn’t buy it and returned quick verdicts. In November 1941 a jury sentenced Browne to eight years, Bioff to 10, and issued each a $10,000 fine. Circella, who had been laying low, was apprehended on December 1, 1941. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to eight years.

During the sentencing, prosecutor Mathias F. Correa described Bioff as a “gangster-

racketeer type who could never be rehabilitated to live a useful life in society.”

The events that followed, however, changed some of their minds about cooperation.

All three received various threats, and some were directed at their family members. According to some accounts, Bioff was more angry than fearful. On February 2, 1943, the warnings escalated into brutal reality.

Estelle Carey, the 34-year-old model, dice girl and girlfriend of Nick Circella, was found murdered in her apartment on the North Side of Chicago. She had been bound, beaten and burned. Some theorized it was a message to Circella, Bioff and Browne. Others believed the assailants were searching for an alleged cache of money and valuables, as Carey was Circella’s “banker.” Regardless of the motive, it was clear that the violent scene was the work of Chicago’s underworld.

Stunning both Hollywood and the Outfit, Bioff and Browne decided to flip.

Bioff and Browne sing

The federal government had discovered more theatrical union corruption nationwide involving specific members of the Chicago Mob. Bioff and Browne’s change of heart would help put away some of the biggest names.

At one point during cross-examination, Bioff said of himself, “I was just an uncouth person, a low-type sort of man. People of my caliber don’t do nice things.” His testimony had dire consequences for the underworld.

Their testimony in 1943 reached straight into the Chicago syndicate’s elites. Among those named were Nitti, Rosselli, Paul “The Waiter” Ricca, Louis “Little New York” Campagna, Charles Gioe, Phil D’Andrea and others.

Nitti, facing inevitable conviction, chose suicide instead, as reported by the coroner. The rest served varying stretches in federal prison. Bioff’s cooperation branded him as the betrayer who shut down the Mob’s Hollywood pipeline and broke the code of silence.

Browne and Bioff got out of prison early in 1944, unlike Circella. Historians disagree on whether Circella and/or his girlfriend cooperated with authorities, but he served his full sentence nevertheless.

In rare praise, Pegler commended Circella’s resolve in a 1953 column: “If you are going to rate gangsters you must proclaim your standards, and all authorities agree that the ideal is a character who keeps a still tongue in his head, never squeals and never begs.”

Circella left prison only to face deportation in 1953. By 1955, initial reports (and many historical accounts since) stated that Circella was shipped off to Argentina. However, Circella ultimately ended up in Mexico and set up operations there. Allegedly, his presence influenced Sam Giancana’s decision to move there after his 1966 release from prison.

According to some sources, Browne, who had a long history of stomach ulcers, slipped into obscurity back in Illinois after his prison release and “drank himself to death” in the early 1950s.

A dynamite finale

After prison, Bioff went to Arizona and lived under an assumed name, William Nelson. He and his wife, Laurie, seamlessly integrated into the state’s social elite. Bioff struck up a friendship with the clever and sophisticated Harry Rosenzweig, a political player with strong connections to the Republican establishment, and even caught the eye of Barry Goldwater, an emerging political figure and department-store heir whose charm and network defined midcentury Phoenix.

Through Rosenzweig, Bioff purportedly donated about $5,000 to Goldwater’s first Senate campaign — a considerable amount back then — and, per contemporary reports, even rode on Goldwater’s private plane. Meanwhile, Bioff’s underworld instincts found a fitting outlet through Gus Greenbaum, the casino operator based in Phoenix and Las Vegas. Greenbaum introduced Bioff to Nevada’s profitable gaming industry, giving him a job as entertainment director of the Riviera Hotel.

On the morning of November 4, 1955, Bioff tended to his usual routine, which included a drive into town to check stock market activity. While his wife watched from the kitchen window, Bioff climbed into his pickup truck and turned the key in the ignition, which triggered a charge wired beneath the seat. He died instantly.

No more than 15 minutes after the massive blast shook the neighborhood, reporters and police arrived on scene. His wife had just turned her back from the kitchen window when the explosion launched shards of glass and framing into the house. “He turned to wave,” she told a reporter at the scene. “He always waved. I waved back.”

Pressing further, the reporter asked if she thought he was a victim of foul play or perhaps was suicidal, to which she replied, “Oh God no!” and added, “He didn’t have an enemy in the world.”

The explosion was so violent that officials could not determine immediately if the blast was caused by dynamite, nitroglycerin or some other components combined.

Rumors soon circulated about recent visitors in the Phoenix area, including then-Chicago Outfit boss Tony Accardo. Police were convinced of one thing — it was a Mob hit.

Three years later, Greenbaum would meet his own grisly end in Scottsdale, found murdered along with his wife in what police called a “vicious underworld settling of accounts.” The Arizona desert, it seemed, wasn’t far away enough for either of them.

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org